Generative AI in Nigerian education: Can technology bridge the country’s learning divide?

GAI

GAI

AI

AI

AI

AI

WHEN

WHEN

APRIL

APRIL

Generative AI in Nigerian education is emerging at a time when the country faces one of the world’s deepest learning crises. A 2024 report estimates that more than 18.3 million children living in Nigeria are out of school, the highest number in the world.

For those in classrooms, conditions remain strained: in rural areas, one teacher is often responsible for more than 100 pupils.

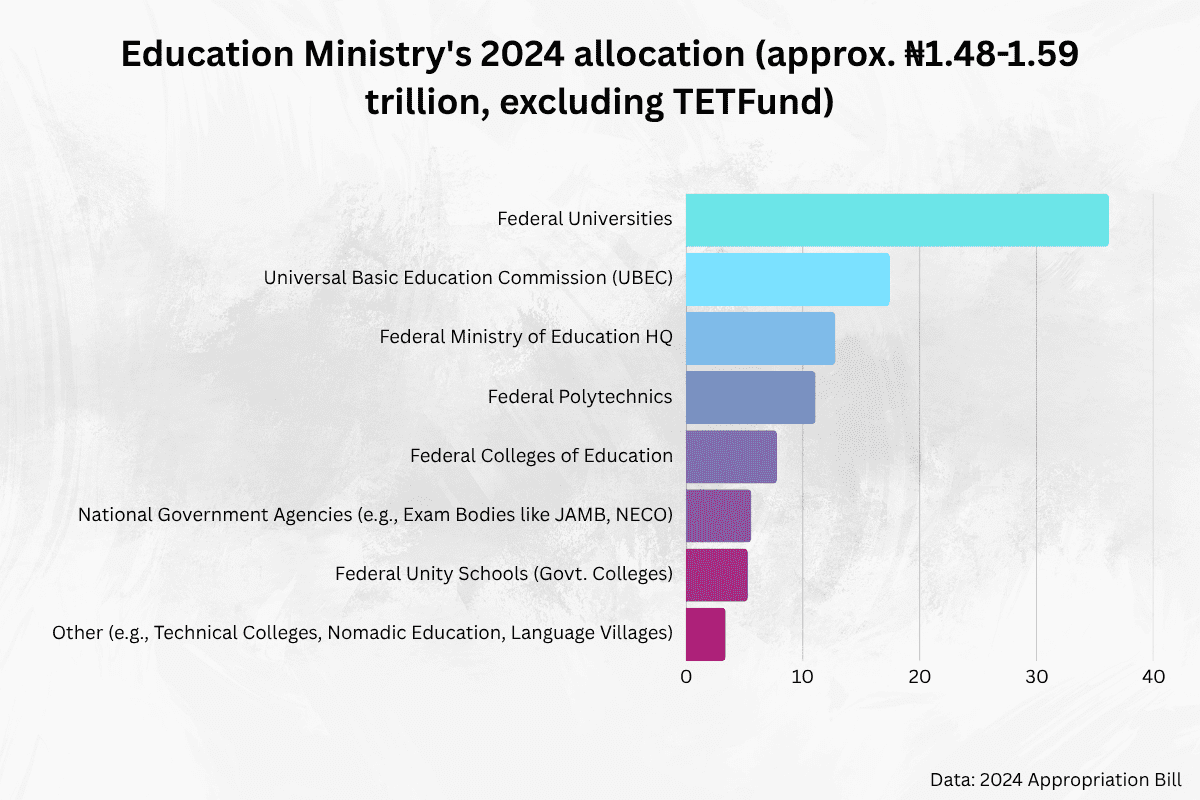

Nigeria’s approved 2024 budget allocated ₦1.59 trillion – about 5.5% of total spending – to education, a significant increase from previous years. Most of the ₦1.59 trillion went to salaries, with limited funding for infrastructure and reforms. Critics say the spending still falls below global standards and cannot match the scale of the crisis.

Amid these gaps, a new layer is being added to Nigeria’s education system. Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot, and African-built edtech platforms are beginning to find their way into classrooms and study routines.

Their arrival raises urgent questions about who benefits, who gets left behind, and whether AI can widen or narrow Nigeria’s entrenched inequities in learning.

The promise of generative AI for Nigerian education

Globally, tools like Khan Academy’s Khanmigo and Duolingo are redefining learning, offering 24/7 tutoring and adaptive lessons that give students support even where teachers are scarce.

In Nigeria, edtech startups are racing to bring those possibilities into reach. uLesson, one of the earliest movers, offers personalised lessons and interactive tests to students across West Africa.

In June 2024, it adopted artificial intelligence (AI) primarily to enhance its educational services by offering an AI-powered homework help feature called “Ask”. It also works offline through SD cards to reach students with weak connectivity.

“There’s still no one doing it at scale, and at the pace needed to address the educational challenges we face on the continent,” said Sim Shagaya, founder of uLesson. “If you think about uLesson as a ‘lesson-teacher-meets-the-smartphone’, then you’ll understand our approach. … This is exactly what we are trying to replicate with uLesson, using the technological tools available now to both students and parents – smartphones and tablets.”

The government has also signalled interest through initiatives like Inspire for Students and Ignite for Teachers to support virtual classrooms and lesson planning.

That vision aligns with Nigeria’s National Digital Learning Policy (2023), which encourages the ethical use of AI “to enhance the effectiveness, efficiency, and inclusivity of digital learning in Nigeria”. At GITEX Nigeria 2025, National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) Director-General, Kashifu Inuwa Abdullahi, described AI as key to unlocking the country’s educational productivity, urging for accelerated adoption in classrooms.

At its best, generative AI offers what traditional classrooms often cannot: real-time, individual attention. In crowded classrooms where one teacher handles dozens of students, AI tools can supply supplementary explanations, practice questions, or feedback; features that help reinforce learning outside school hours. For learners in remote areas or in schools with fewer resources, these options could be a game-changer.

Private innovators are driving early experiments, while NITDA and the Education Ministry draft frameworks to guide responsible adoption.

The promise is that generative AI could offer scalable, affordable, and adaptive educational support, bridging gaps that traditional systems have struggled to close. But for this potential to be realised, access, cost, and equity must be part of the equation, not the afterthought.

Equity gaps: Who gets left behind?

For all its promise, the spread of generative AI across Nigeria’s education system mirrors an old story of access. The same infrastructure gaps that keep millions of children out of school now threaten to determine who benefits from the digital classroom and who is left out of it.

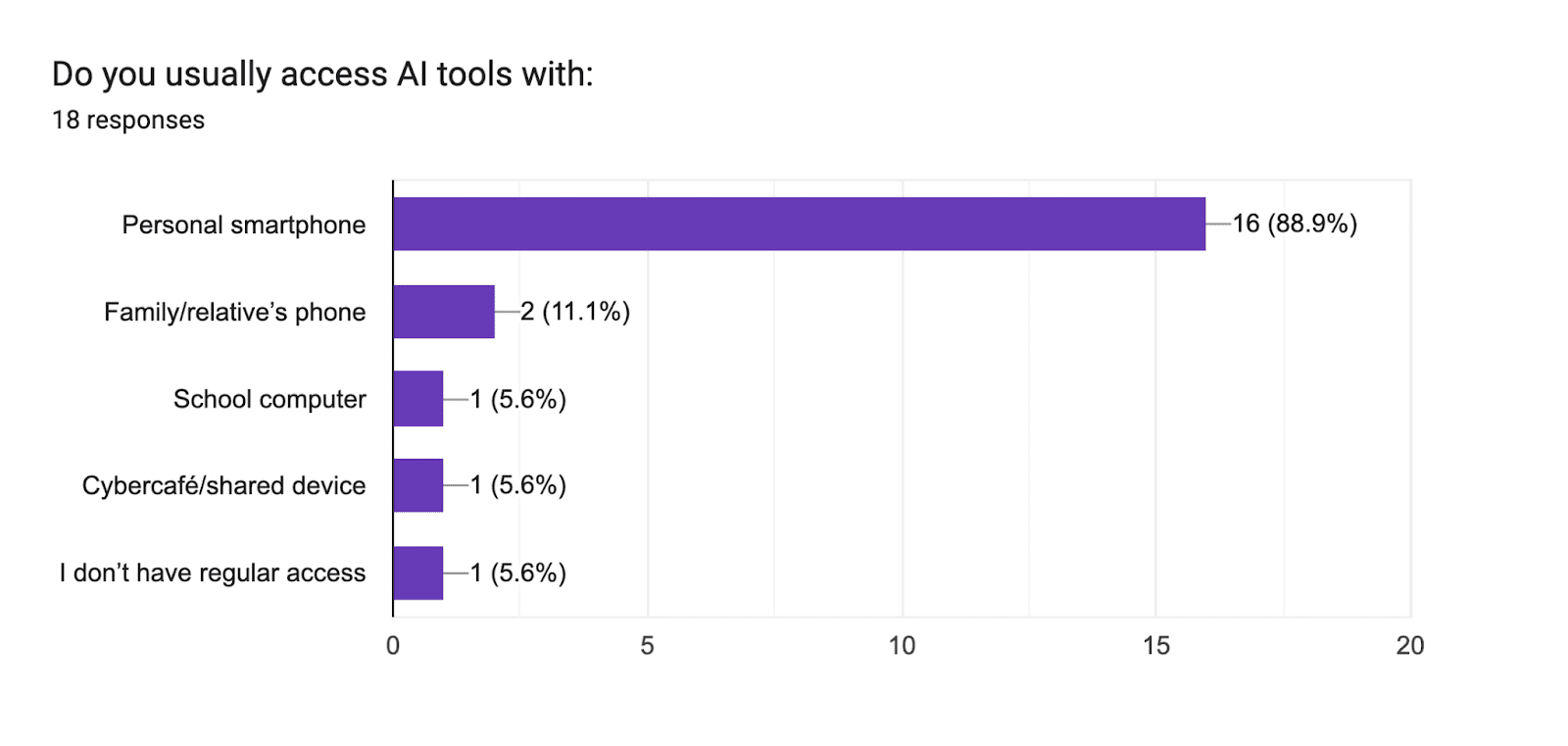

According to the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), broadband penetration was only 48.15% percent as of April 2025. In rural areas, that figure drops sharply, as many communities still depend on weak or inconsistent mobile signals. The cost of data remains another barrier. In a country where many families live on less than ₦1,000 a day, streaming a five-minute video lesson can easily compete with the price of a meal.

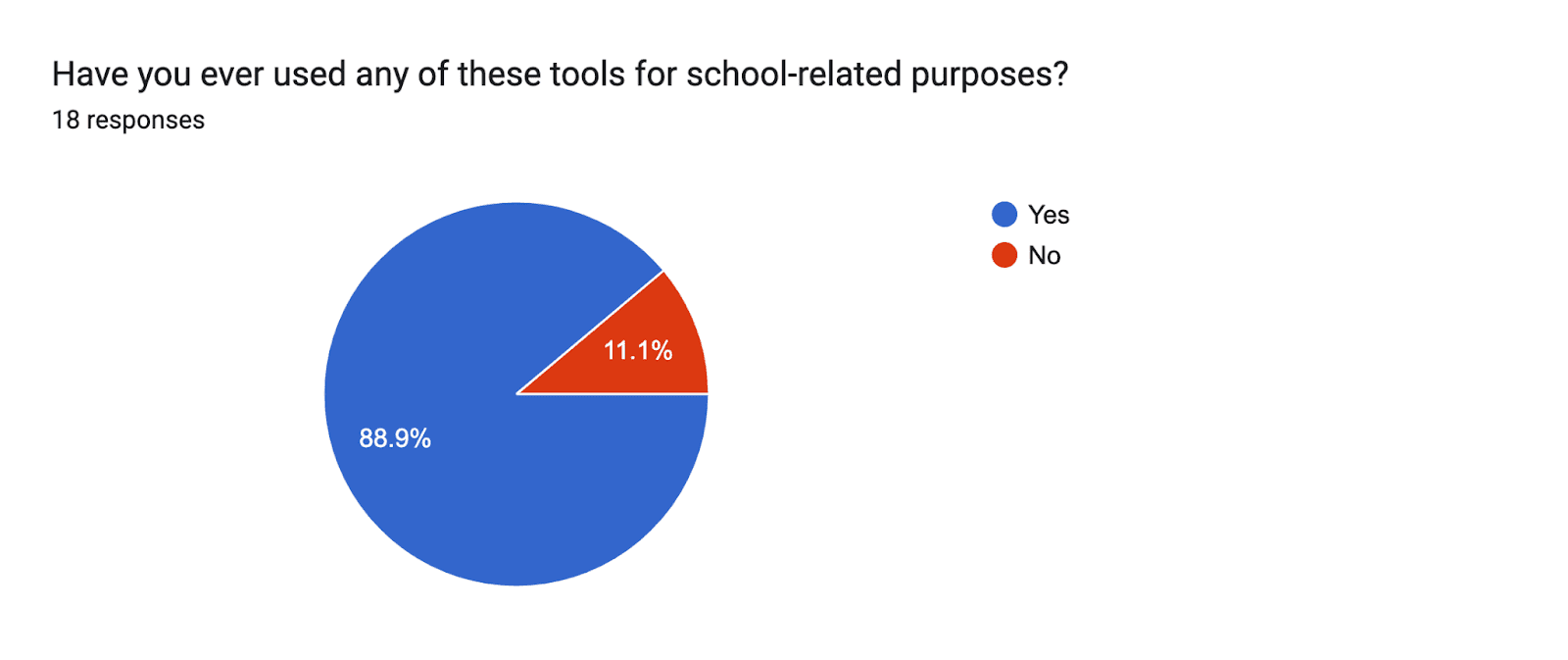

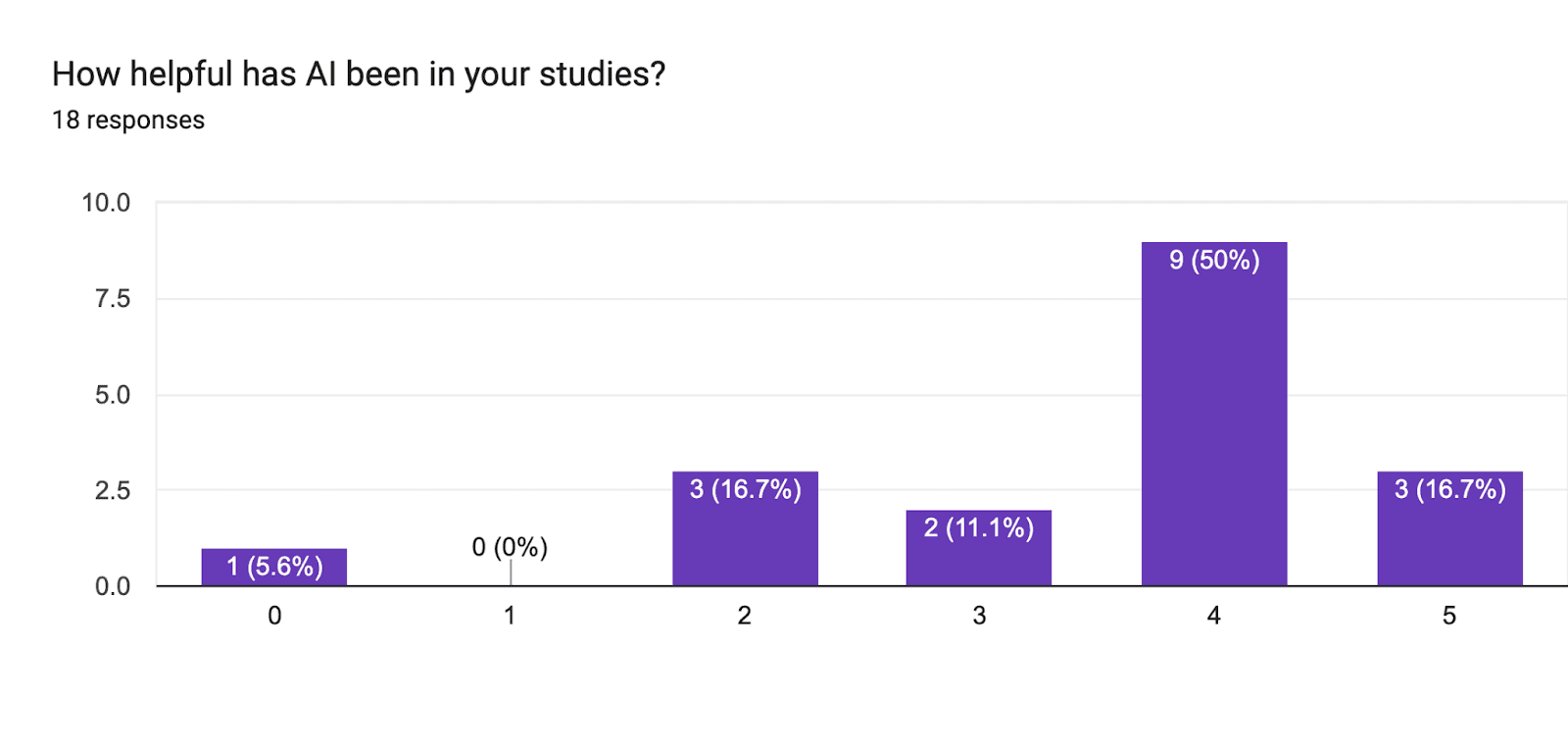

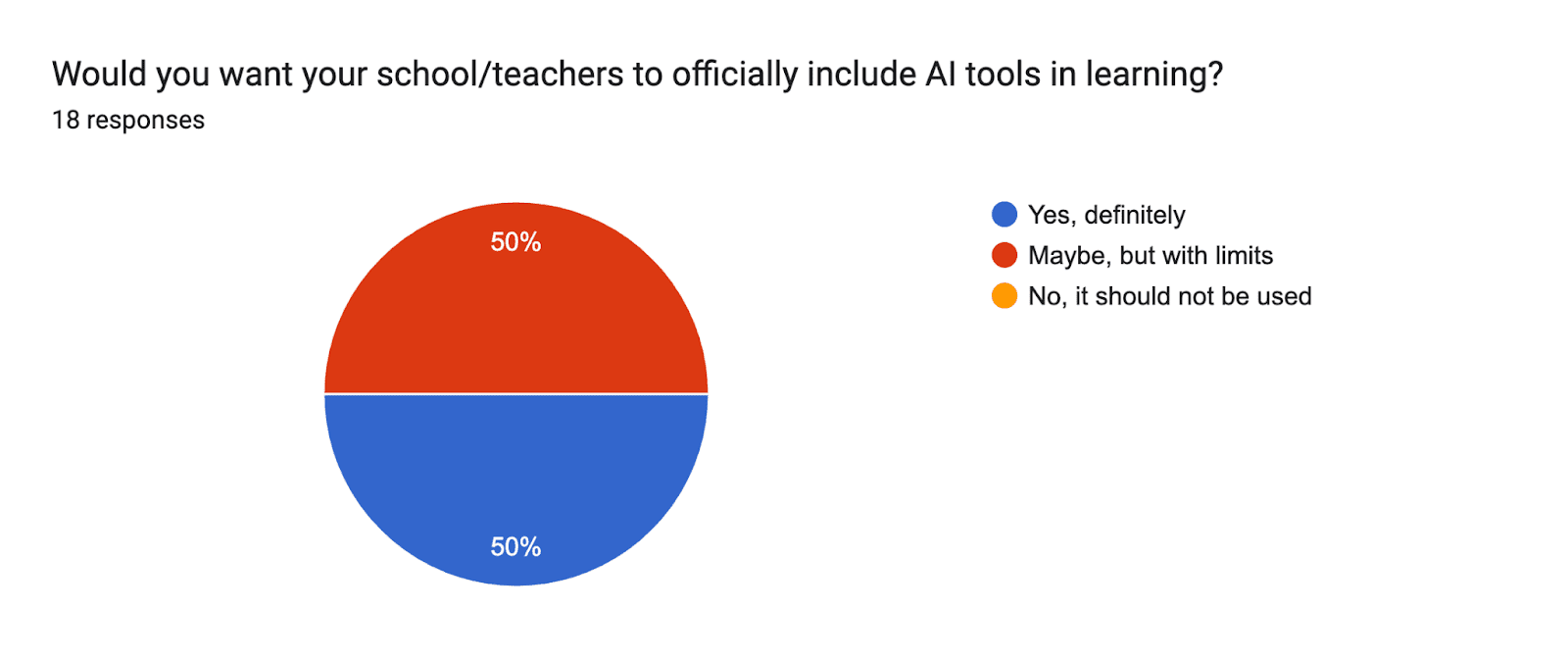

These realities are echoed in the voices of the 18 students surveyed for this story. While some spoke enthusiastically (50%) about how helpful AI has been in their studies, another 50% said AI has confused them in their studies.

A university student in Ibadan said, “AI has made my schoolwork faster and more engaging. I use ChatGPT to get feedback on my essays.” But a respondent from Kano countered, “Sometimes even accessing the school portal is hard, not to mention AI apps.”

Language remains a barrier. Most AI platforms are built in English, while many rural students learn in Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, or other local languages. Translation and localisation could make AI more useful for them.

Experts say localisation is critical if generative AI is to reach all learners. Ayoola Akinyeye, Director of Schools at Chrisland Schools, told Premium Times that “AI should be embedded in Nigeria’s curriculum not just as a subject but as a tool for teaching across subjects,” warning that “adoption must go beyond tech hype to meaningful, contextual use.”

uLesson has already adapted its content to local curricula and offline use, showing how localisation can help students without strong internet.

A student from Kano explained, “It is easier for me to use the AI when I ask in English, but sometimes it does not understand my spelling or accent.” For learners like him, AI tools often reinforce a digital divide rather than close it.

There is also the question of exposure. Some private schools in Lagos and Abuja have started integrating AI chatbots into lesson plans, while teachers in public schools say they are still struggling with basic resources like electricity or chalk.

In the survey, a teacher from Ogun State put it simply: “We do not even have enough textbooks, not to talk of computers.” Another respondent from Kaduna added, “AI can help, but only when it reaches the public schools. For now, it is for the rich.”

This divide between those who can and cannot access AI mirrors Nigeria’s wider digital inequality. Without phones, steady power, and affordable data, AI remains an idea rather than a tool.

Yet there is optimism. A student at the University of Lagos said she believes AI can “help students in villages if the government provides support.” Her view captures a wider sentiment from the survey: students are not rejecting technology. They want inclusion – cheaper data, better connectivity, and AI that speaks their language.

Generative AI may hold the potential to make learning personal for millions of Nigerian students, but unless the tools are designed for real-life conditions – patchy internet, low budgets, and multilingual classrooms – it could widen the education gap it promises to close.

Asked about accuracy and trust, only a third of respondents said they fully trust AI-generated answers. Several added that they “double-check with textbooks” or “ask lecturers” before using AI material in assignments.

The data also suggests an emerging urban-rural digital divide: students in urban schools reported more access and familiarity with AI apps, while those in rural or public institutions often had little exposure.

Accountability questions

As AI enters classrooms, accountability questions grow: who regulates its use, protects student data, and ensures it improves learning?

Nigeria does not yet have a national framework that governs how artificial intelligence is used in education. The National Artificial Intelligence Strategy (NAIS), still in draft form, focuses broadly on innovation, jobs, and governance – not the classroom.

The National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), which oversees digital policy, included education under its Strategic Roadmap and Action Plan (SRAP 2.0), but experts say implementation remains vague. There are no clear rules yet for how AI systems should handle student data, provide transparency, or protect minors from algorithmic bias.

UNESCO also warned that the rush to integrate AI into education without safeguards could deepen inequities.

A teacher from Lagos said in the survey, “We are being told AI will help us teach better, but nobody has explained how or trained us to use it.” The concern is not just about technology replacing teachers but about teachers being left out of the design process altogether. As one respondent put it, “AI cannot replace us, but it can make us invisible if we don’t know how to use it.”

This unease echoes broader conversations worldwide. Audrey Azoulay, UNESCO’s Director-General, has said that governments “must ensure teachers remain central to the learning process even as AI becomes more present in classrooms.”

Beyond the classroom, the issue of data governance is becoming critical. Generative AI platforms rely on massive data inputs – including student essays, personal information, and interaction histories – to personalise learning. Without regulation, such data could be misused for commercial purposes or even leaked.

Dr Kashifu said data protection ‘must be at the heart of Nigeria’s AI agenda.”

Still, enforcement remains weak. The Nigeria Data Protection Act (2023) provides some legal coverage, but there are no established penalties for misuse of learning data, nor standards for what AI-driven education platforms must disclose to parents or students.

Funding and accountability are also intertwined. Many AI education pilots are donor-driven or privately funded, raising the question of whose priorities they serve. Are they solving Nigeria’s learning crisis or creating another dependency on imported tools?

A Lagos-based education analyst, Abiola Sanni, noted in an interview that “AI tools must fit our classrooms, not the other way around,” adding that “without local content policies, we risk turning Nigerian schools into testing grounds for foreign software.”

Experts and teachers agree that AI’s future in Nigerian education will depend not only on innovation but on governance – policies that define ownership, transparency, and ethical use. For now, those rules are still being written, and many classrooms are already experimenting without a map.

The effects of AI in Nigeria’s education sector are already being felt in very different ways, depending on who you ask.

In Lagos, some private schools are experimenting with AI tutors. A Kano student said, “Most of my classmates can’t afford data,” highlighting how quickly these experiments become a story of access and privilege.

Among the students who responded to this survey, nearly half said they have used generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Copilot for assignments or exam preparation. A 200-level student at the University of Lagos said, “AI helps me break down complex topics and write outlines faster. It feels like having a tutor available anytime.”

Data costs remain among the highest in Africa relative to income.

Teachers are also navigating this shift with mixed emotions. A secondary school teacher in Abeokuta said she encourages her students to use AI “for summaries and explanations,” but added, “I worry about accuracy. Sometimes the AI gives wrong answers, and students accept it as the gospel truth.”

But the optimism meets a harder reality in Nigeria’s rural areas. A 17-year-old in Ibadan said, “We’ve heard about these apps, but our teachers tell us to focus on textbooks because there’s no Wi-Fi in our school.

Generative AI and the future of education in Nigeria.

AI can make education more inclusive, but only if backed by policy, infrastructure, and teacher training. It will not educate 20 million out-of-school children today, but it could ensure the next 20 million are not left behind.

It offers tools that can personalise learning, translate lessons into local languages, and help teachers manage large classrooms more efficiently. But without deliberate policies and investment in infrastructure, AI may deepen existing inequalities rather than resolve them.

Dr Bosun Tijani, Minister of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy, backs this point.

For AI to make a real difference, policymakers must ensure that access is not determined by geography or income. This means developing offline learning models, expanding broadband coverage, and integrating indigenous language interfaces so students in Abeokuta and Sokoto can use the same tools as those in Lagos or Abuja.

There is also a need for teacher training and ethical guidelines. If AI is to assist, not replace, teachers, then educators must be part of the design and deployment process.

The difference will depend on choices made today: whether Nigeria builds an education future driven by equity and accountability, or one where algorithms simply mirror the inequalities they were meant to solve.

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate