“The machine now speaks our language”: How Nigerian AI Developers are building a more inclusive future

AI

AI

AI

AI

WHEN

WHEN

GUARD

GUARD

WOULD

WOULD

The availability of open-source datasets for many African indigenous languages by local developers (like NaijaVoices) marks a significant advancement in digital inclusion. This has afforded many African students, researchers, language instructors, and small business owners access to trained Natural Language Processing (NLP) models capable of understanding and generating texts in local languages.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now a lasting feature in the global landscape. Since its adoption across Africa, particularly in Nigeria, it has rapidly transformed sectors such as health, education, and finance. Yet, for many Africans, access to these technological advancements remains challenging, as most existing AI models lack cultural awareness, competence, and local language understanding.

Nigerian AI researcher and specialist, Chris Emezue, is the founder of NaijaVoices, a community-driven initiative designed to expand local language access in global AI development. Reflecting on the project’s origin, he recounts:

“I wanted to build a large, meaningful dataset for Nigerian trade languages. Before NaijaVoices, existing datasets were limited, five hours here, 50 hours there.

“I was surprised to find no speech datasets for Igbo, despite assuming otherwise. Many people told me they abandoned projects in their language due to a lack of data. So I decided to change that by building one with the community.”

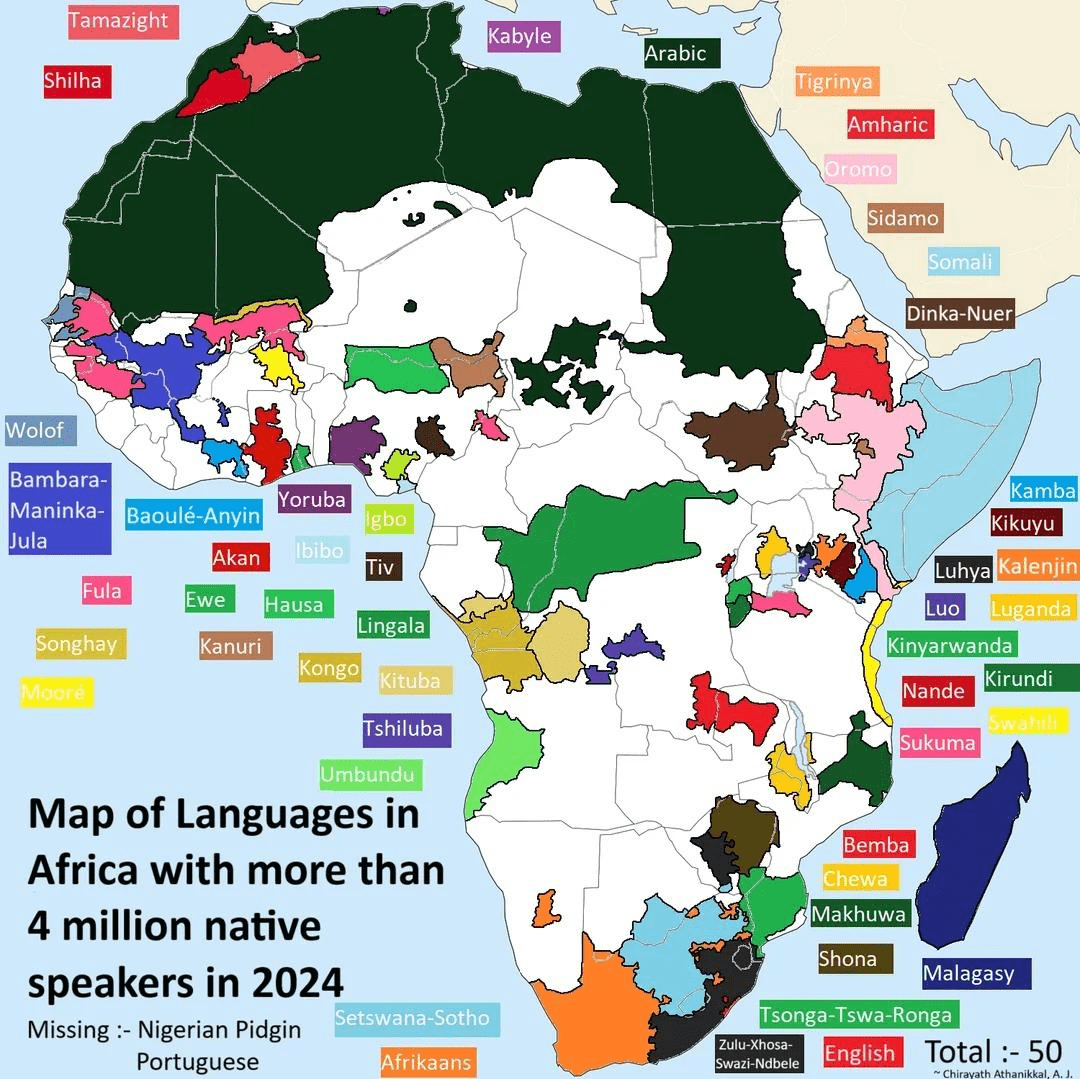

Housing fifty-four sovereign countries with over two thousand languages, Africa is the second largest continent by landmass and population (only after Asia) and home to about 1.5 billion people, roughly 19% of the world’s population. Despite its rich cultural diversity and abundant natural resources, Africa confronts challenges in sustainability, technological advancement, and infrastructural development.

This observation indicates that Africa’s slow adoption of technological innovations, such as AI and automation, cloud computing, and digital technologies, is due to various challenges in its nations.

Read also: Algorithm and Hustle: How AI-powered digital platforms affect informal trade

Although technology has had its roots in Nigeria since the ‘50s, the telecom and internet revolutions did not come until the 2000s, ranging from foundational satellite to mobile and now fintech.

The adoption of AI in Nigeria is significant. Since the introduction of large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini (formerly Bard), LLMs are now being integrated into everyday technologies and across various sectors such as healthcare (for diagnosis, prescription tracking, etc.), education, and even journalism (as done by Dubawa in their new and innovative AI-based fact-checking models).

However, a critical gap is that most of these models are based on the English language, which ignores the prominence of local languages, therefore widening the digital literacy and digital divide gaps across Africa.

There are over 500 Nigerian languages, with Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, and Nigerian Pidgin being the most widely spoken. However, none of the models use Nigerian languages in their Natural Language Processing (NLP) or Machine Learning (ML) structures, or even in the development of Application Program Interfaces (APIs).

Nevertheless, a team of Nigerian developers are working to create Large Language Models (LLMs) and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) that use Nigerian languages as the base of their data through NLP. Their work is notable for producing original datasets that are originally generated in Nigerian languages.

This implies that there is no adoption of existing frameworks, such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, DeepSeek, etc., but rather on manually collected data from real Nigerians, which is then used to develop their models.

Such work holds tremendous significance because it puts Nigerian languages, including minority languages like Igala and Fulfulde, in the global space. This model also facilitates the development of additional APIs. Chris explains how these datasets can be useful for bigger and even multiple projects in the future; he said:

“What NaijaVoices is trying to do is to give people what they need to build what they want to build, from translation engines to speech recognisers and chatbots. So now, anyone that wants to build a voice assistant or any speech-based project now has something they can start from.”

Lanfrica and Naijavoices Community

African language resources are often difficult to find, and changing that narrative is Lanfrica’s mission. This user-friendly online platform brings together valuable research, datasets, and projects on African languages and makes them easily accessible to students, developers, and language enthusiasts. Lanfrica, more than just a database, addresses the scarcity of local language data.

Lanfrica (pronounced lan-frika), conceived in 2020, is an open-access, community-driven platform, projected to solve this discoverability problem. It offers a simple, searchable database that connects African language researchers, datasets, and tools in one place.

This start-up by a team of developers was co-founded by Chris Emezue and Bonaventure Dossou, a Nigerian and a Beninois, both researchers at McGill University, Canada, with a vision to empower researchers and local contributors to preserve and promote African languages in the growing field of artificial intelligence.

However, in 2021, with a grant from the Lacuna Fund, the NaijaVoices project was launched, which seeks to address the scarcity of speech datasets for Nigerian languages. Chris said that “African languages are mostly oral. Our traditions, our stories, and even our everyday communication rely heavily on speech.”

He further highlighted the project’s importance by stating, “It is important if you want to build technology, specifically effective technology for Africans, to incorporate a speech component, as many of us prefer to communicate verbally.”

While this is largely true, language barriers and biases constitute one of the factors hindering the adoption of AI in Africa; however, when Chris’s team began their work, speech datasets for most Nigerian languages simply did not exist. “People wanted to build projects in Yoruba or Igbo, but they could not find the data, so they abandoned them,” he recalled. “I wanted to change that.” With the NaijaVoices project, Chris and his team set out to create a large, high-quality, and culturally aware speech dataset.

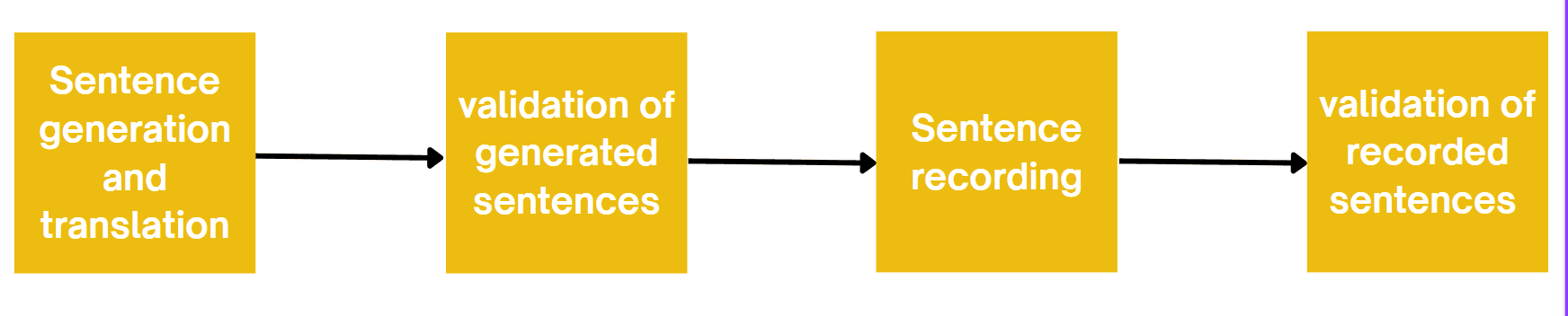

Numbers and quality matter: the datasets created followed a simple yet rigorous methodology. Over five thousand diverse speakers were engaged across various Nigerian languages. The first set of languages they worked with was the three main Nigerian languages: Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba. Original sentences were created by the participants/community members and translated into English to avoid inaccurate machine-based translation.

Following translation, the sentences are organically validated, errors are corrected, and the next stage is sentence recording. The sentences were also recorded by several people across different parts of Nigeria and multiple age grades, thereby allowing for diversity in the data. The recorded sentences (audio outputs) were then validated before being adopted for potential use.

NaijaVoices aimed to be robust enough to support real-world applications, unlike previously available datasets on Nigerian languages, some of which were as small as five hours. Even more critically, over five hundred Nigerian volunteers wrote all sentences from scratch to ensure cultural relevance.

About 5,000 diverse speakers recorded the dataset and contributed around 1,800 recording hours, bringing the available dataset to an average of about 3.7 million. In all, more than 1,800 hours of accurate sentences in local languages were recorded.

Securing funding to execute large-scale programmes is not usually easy, especially in Africa, where the prevalence of the digital divide complicates the problem. The team won the 2021 Lacuna grant for machine learning, which was able to help them kickstart the project.

Nevertheless, as with many projects like this across Africa, sustainability is a big concern. Chris expressed concerns about the funding hurdles with the project, saying the journey has only been challenged by a lack of funds. “We got our initial grant from Lacuna Fund, but it was not enough to pay people what their work was worth.” Much of the early work was voluntary, motivated by the passions of individuals who wanted to see their languages represented.

Chris further added that “so I guess challenges in building speech data sets for Nigerian languages – number one is funding. We got funding for the NaijaVoices data set.

“Then I think last year we applied again for funding to build a second version of another project with the NaijaVoices community, and this project was even better. It was like, instead of reading the text, you generate the text naturally. And it was really an amazing project that we were applying for funding for. But guess what? We didn’t get funding for that one.

“So, this is the fact that funding is not guaranteed; this year, you could be lucky and get funding from here, but next year, you don’t know where you’re getting funding from. And the other thing is that there are not many people who are supporting this.

“Big tech can throw away billions of dollars to invest in scaling AI and pro-profit models, but there are not many people who are supporting, financially, non-profit community-led organisations. We live in a world where no one wants to give anything for free.”

Every project’s core is determined by the individuals who stand to gain from it. While speaking, Chris highlighted that both Lanfrica and NaijaVoices are designed to empower specific groups.

“The beneficiaries of the project are students and researchers looking to build AI models in their native languages, local companies and SMEs developing speech and language solutions tailored to Nigerian users and community members who contribute to the datasets and receive financial and career support in return. We are trying to empower them. That empowerment could be financial, it could be career related.”

While the dataset now benefits many tech companies and still has the potential to benefit developers across multiple sectors like health, journalism, education, and infrastructure, international tech companies and local businesses now consult the dataset for their development.

He added that “since the launch of the platform, the response has been strong. The NaijaVoices dataset has been downloaded over 500 times in the last month alone, with new sign-ups each week. Users range the data being used by a range of entities, from small Nigerian businesses to international tech companies, including music companies that work in Igbo and Yoruba, to build AI tools for local communities.”

Chris added that while users benefit from the dataset, NaijaVoices also empowers local innovators through its Language Heritage Micro-grant. Funded by donations from commercial access to the dataset. The microgrant supports community-led language projects.

“We created a licensing model where commercial users donate to access the data,” he explained. “One rule we set was that any accepted proposal must include at least one person from the Naija community who worked on the NaijaVoices dataset. It’s a chance for them to create a dataset for another language. That way, we’re giving back to the community.”

In a push to preserve Nigeria’s lesser-known languages through technology, Gamaniel Adeyemi, a graduate of mass communication, Ahmadu Bello University, is leading a grassroots initiative to document the Gbagyi language using artificial intelligence. As a recipient of the one million naira (#1,000,000) NaijaVoices microgrant,

Adeyemi is building a six-hour text-to-speech dataset under the project titled “Future-proofing Gbagyi: A Community-centred Approach To Language Data Collection”. He described the idea of the project as going “into the Gbagyi community and get conversational-style audio and transcribed texts”.

“The language I submitted is endangered and underrepresented, and that played a big role in my proposal.”

Read also: African health tech funding rose by 5400% in Q2 as global funding declines

Adeyemi’s journey into language tech began with NaijaVoices. Before joining, he had no experience in data collection for AI, but his involvement changed everything. “NaijaVoices was the beginning of it all,” he recalled.

“At first, I didn’t even know why I was doing the project. But over time, I understood that the data we were gathering could teach machines how to speak and respond in African languages.” He is now expanding his work by collaborating with Mozilla Common Voice to build accessible tools for collecting voice data in local languages.

He believes the future of technology in Africa depends on language inclusion. “Technologies become somehow useless if they’re limited to English,” he said.

“We have phones and cars that respond to speech, why can’t they understand Yoruba or Igbo?” Adeyemi called on the Nigerian government to support language-based innovation through policy and funding. “There’s manpower and excitement among young people. The only thing missing is government support,” he added.

For Adeyemi, the goal is not just to create new tools but to ensure existing technologies reflect Nigeria’s linguistic diversity.

Despite the funding hurdles, Chris remains committed. He envisions a future where Africans, not just big tech companies, will drive AI, building it for their benefit. “If we do not take the lead in developing AI for our languages, someone else will, and they might misrepresent us or leave us out entirely.“

One of the volunteers, Abideen Amodu, shared his experience and motivation to have participating in the project; he said,

“A lot of the apps and tools we use daily don’t understand Yoruba, Igbo, or Hausa properly, and that’s because the data just isn’t there. So contributing translations and recordings means we’re helping to build that data from scratch. It’s cool to imagine that, maybe a few years from now, someone could ask their voice assistant a question in Yoruba and get a proper response. It’s like we’re laying the groundwork for that kind of future.”

Amodu was visibly excited about the project when he was first introduced to it by a friend, attributing his enthusiasm to the collaborative structure and governance behind its execution. “It was some sort of community thing. They also organised lectures and training for us, which helped us to understand the importance of the project and its entire connection to salvaging Nigerian languages and the AI race,” he recounted.

Although he participated in voice recording reviews and sentence verification, having contributed several organic words. Despite the prospects, the major challenge he reported to have encountered included translating everyday scientific, financial, business, arts and cultural terms into Yoruba.

He said, “I would say a few things could be improved. First, more structured support for difficult categories like science and finance will be helpful. Sometimes it felt like we were all guessing, especially when there was not already a popular Yoruba word for a term. People working on Hausa and Igbo also had their moments.”

While the feedback on the project is generally good, there is undoubtedly a need for improvement to accelerate Nigeria’s position in the AI race.

Isaac Prosper, a Nigerian and beneficiary (user) of the project, recounted having been introduced to the project when “we (my friends and I) were trying to create a text-to-speech (TTS) model for a medical app that uses Nigerian languages. Our focus was actually on the three main languages and just maybe, Pidgin along the line, but we could not find datasets that matched what we needed at that time until someone told us about NaijaVoices.”

He further explained that “TTS tech (text-to-speech technology) can help blind people use any application. For example, if you have ever seen a blind person use a phone, it is TTS that they use. It reads out the command, and they know what to do after. Yes, that is improving inclusivity in tech.”

Prosper gave an instance of the shortage of technologies that recognise Nigerian Pidgin despite having over 100 million speakers: “We also wished that there was something in Nigerian Pidgin. Many people speak Pidgin – more than 100 million people. It is a whole lot of people speaking one language. And having datasets in that language would go a long way.” While this gap is currently being covered, Dubawa’s AI tool can transcribe Nigerian Pidgin accurately, but there is still a shortage of available technology to user ratio.

Efforts to reach the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) were unsuccessful, as the agency’s spokesperson, Hadiza Umar, had not responded at the time of filing this report. However, in a report published by The Guardian Nigeria, and in line with the growing call for culturally grounded digital innovation, NITDA reiterated its stance on responsible technology deployment.

Speaking on behalf of NITDA Director-General Kashifu Inuwa, Barrister Emmanuel Edet, Acting Director of Regulation and Compliance, stated: “Technology is inherently neutral; it is neither beneficial nor harmful in isolation, but depends on the intent and strategy behind its usage.”

He further emphasised the agency’s policy direction, adding to be an advocate for implementing robust policies and fostering collaborations to ensure technological innovations align with Nigeria’s cultural heritage and developmental goals. This perspective mirrors the mission of NaijaVoices, which aims to ensure AI tools are applied not only for innovation but also for the inclusion and preservation of Nigeria’s indigenous languages.

By Ayobami Olutaiwo

CJID AI and Tech Reporting fellow

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.